Why do smart professionals feel embarrassed that public speaking is still hard?

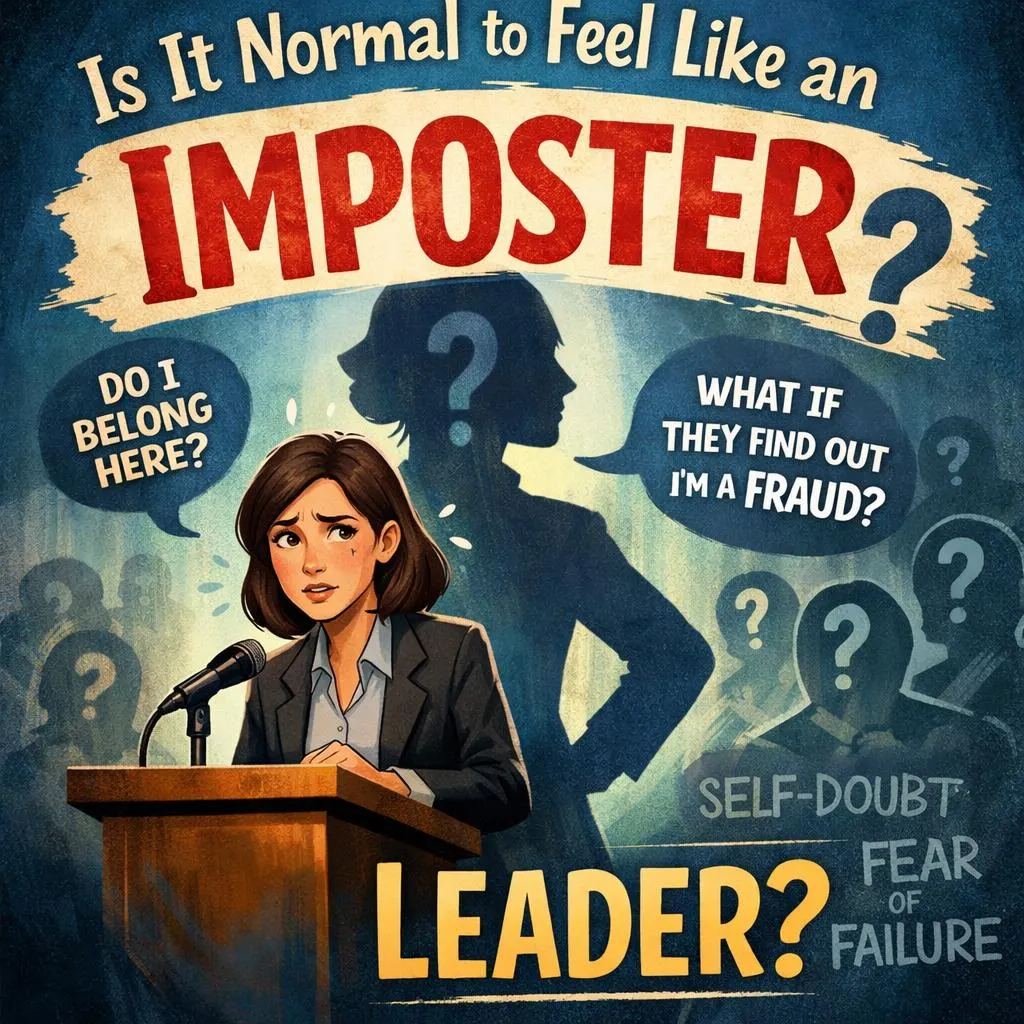

Many smart professionals carry a quiet embarrassment about public speaking; they’re intellectual, respected in their field, and they solve complex problems for a living.

So when speaking still feels hard, the internal story kicks in:

“I should be better at this by now.”

That embarrassment doesn’t come from failure... It's a misunderstanding of how speaking actually works.

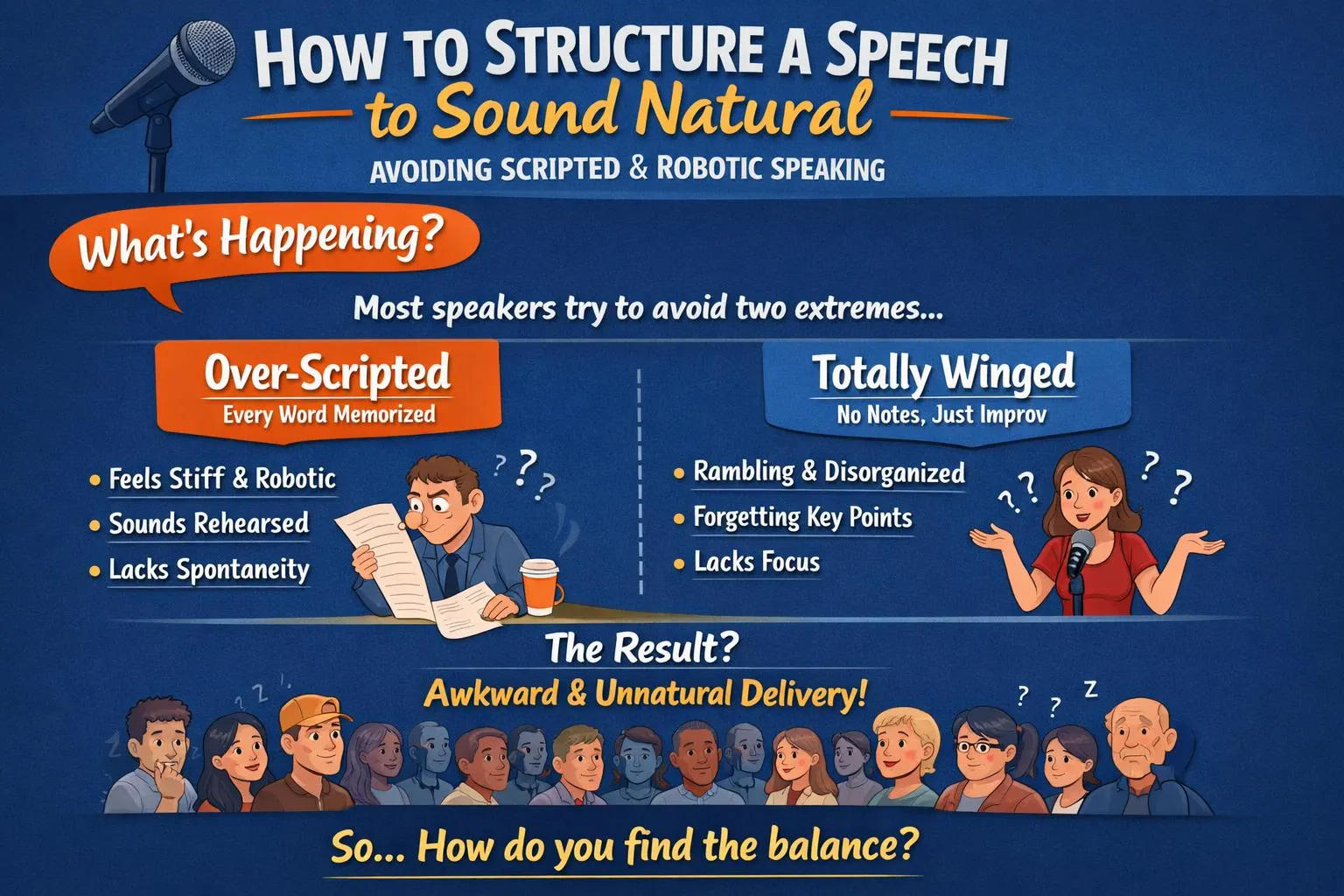

What’s Actually Happening

Smart people often think in dense, layered, nonlinear ways, where ideas connect quickly and insights stack on top of each other.

But speaking out loud requires something different.

When you speak, you have to:

- distill complex ideas into linear language

- choose what matters most in the moment

- monitor how you’re being understood

- do all of this in real time, under observation

High intelligence often means higher self-awareness, which increases self-monitoring.

And self-monitoring increases cognitive load.

Research on working memory and stress under social evaluation shows that this combination interferes with verbal fluency, even when the underlying ideas are strong (Baddeley, 2003; Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004).

In other words:

Your ideas aren’t unclear.

The system you’re using to express them is overloaded.

That overload feels like embarrassment.

The Common Misdiagnosis

Most people misread this experience.

They assume:

- “If I were actually good at speaking, this wouldn’t be hard.”

- “Other people don’t struggle like this.”

- “I must be missing some natural talent.”

So they respond by:

- staying quiet unless they’re fully prepared

- over-rehearsing simple points

- avoiding situations where they might sound unpolished

This turns a skill gap into a character judgment and personal embarrassment.

The Reframe

Public speaking difficulty has very little to do with intelligence.

It has everything to do with externalization.

Speaking is not the act of displaying finished thoughts.

It’s the act of building clarity out loud.

Smart people are often excellent internal thinkers but undertrained external thinkers.

That doesn’t make you bad at speaking.

It means you’ve been practicing the wrong part of the process.

Once you understand that, embarrassment stops being personal.

It becomes technical.

And technical problems are solvable.

What to Do Instead

Instead of trying to sound polished, train yourself to sound oriented.

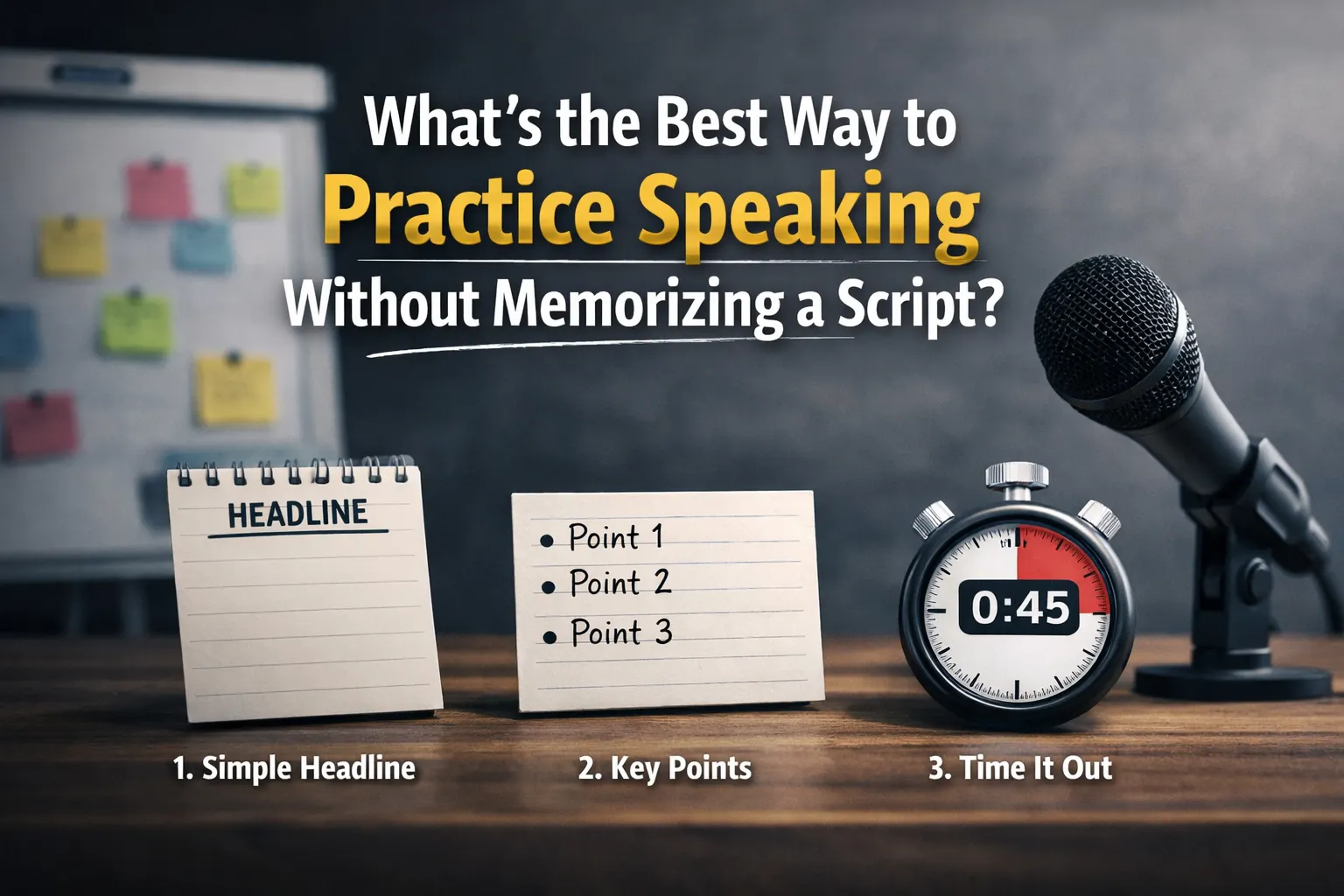

Here’s a simple exercise you can use immediately.

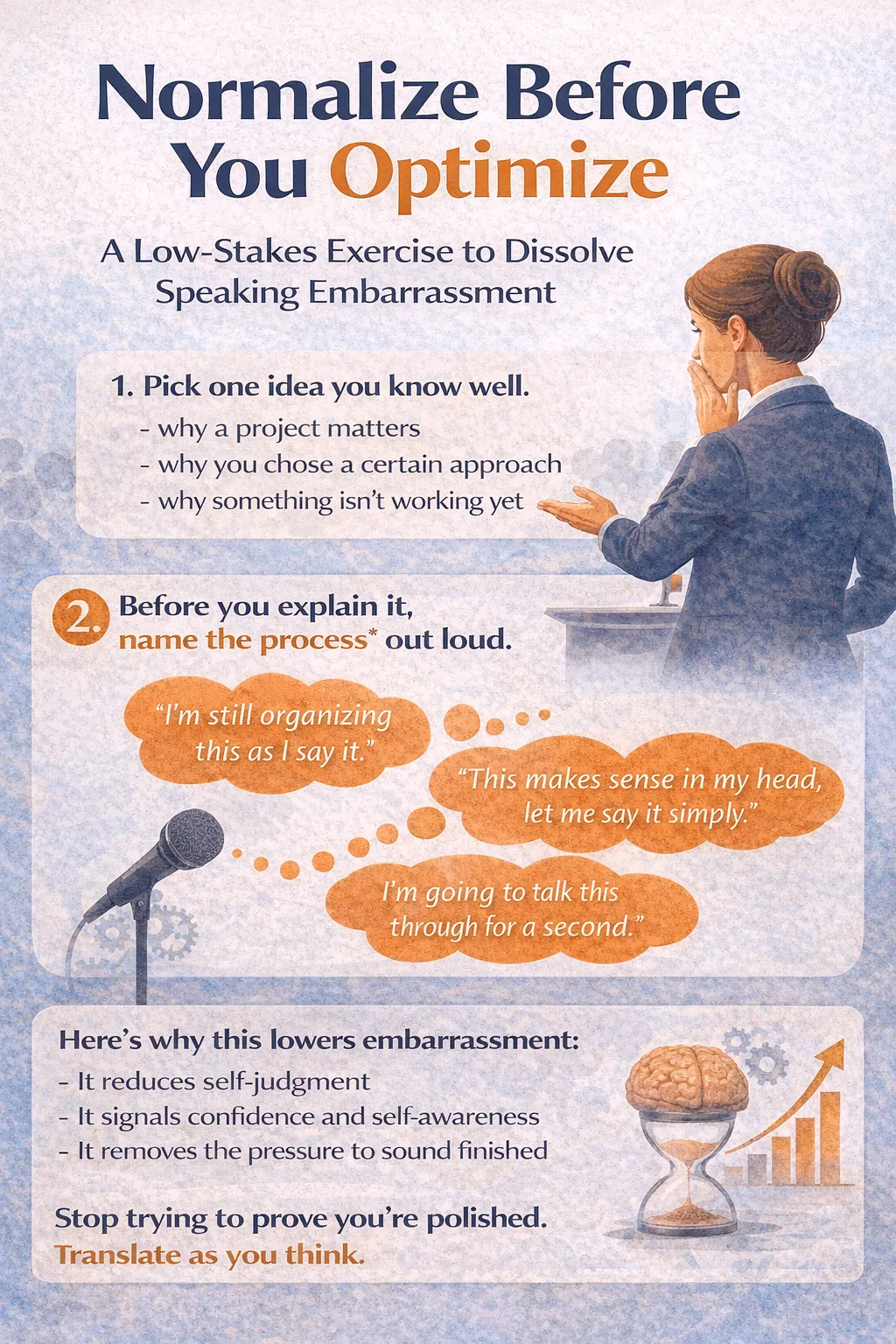

A Practical Exercise: Normalize Before You Optimize

In your next few conversations, do this on purpose, even if you know the subject you are talking about.

Before you explain it, say one sentence that names the process.

Examples:

- “I’m still organizing this as I say it.”

- “This makes sense in my head, let me say it simply.”

- “I’m going to talk this through for a second.”

Then explain the idea anyway.

Here’s why this works:

- It lowers internal pressure to perform.

- It reduces cognitive load by removing the need to sound finished.

- It signals confidence and self-awareness, not weakness.

- It gives your brain permission to organize ideas through speech instead of before it.

Studies on working memory show that reducing self-imposed performance demands frees up cognitive resources and improves verbal clarity under pressure (Baddeley, 2003).

In plain terms:

When you stop trying to prove you’re smart, your intelligence becomes easier to hear.

Repeat this exercise in five low-stakes conversations.

Not to sound better, but to stop treating thinking out loud like a failure.

The Broader Implication

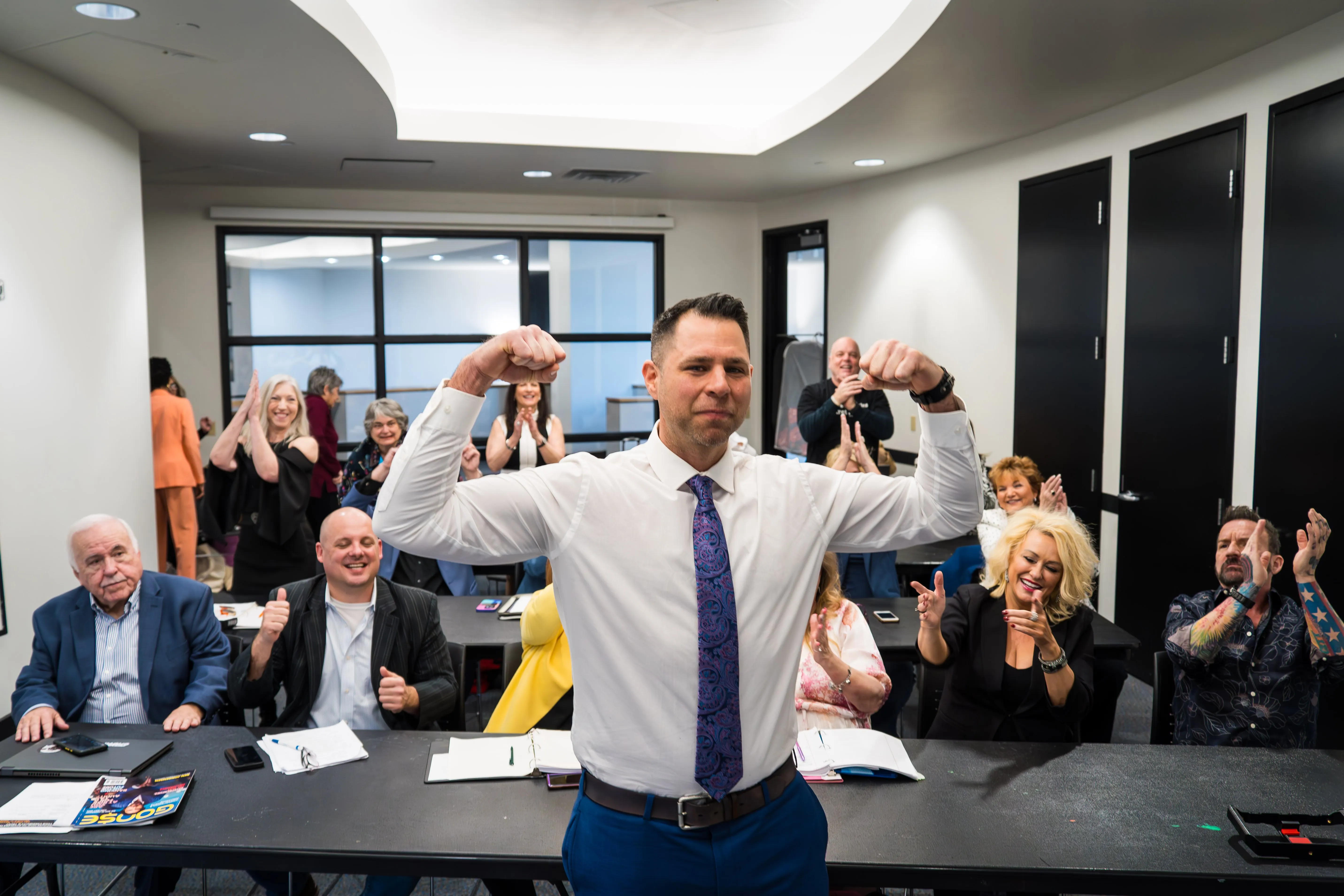

When smart people stop being embarrassed by unfinished speech, something shifts.

They speak sooner, invite dialogue instead of judgment, and their ideas land not because they’re perfect, but because they’re present.

And that’s what people actually trust.

Embarrassment fades when you realize public speaking isn’t a test of intelligence.

It’s a practice of translation. And translation improves with use.

Sincerely,

Devin

Related Posts

- Why do confident professionals freeze when they have to speak out loud?

- Why do I sound clear in my head but messy when I speak?

- Why does speaking feel harder as my role gets bigger?

- Is public speaking anxiety a confidence problem or a training problem?

- Why do I ramble even when I know my topic well?

- How do I stop overthinking every sentence when I speak?

For more resources and coaching, visit:

Cited Works

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: Looking back and looking forward.

https://home.csulb.edu/~cwallis/382/readings/482/baddeley.pdf

Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research.